Communities

Communities

The Derwent Valley World Heritage Site nomination contains within its 24 kilometres (north to south) four industrial settlements. It extends from the edge of Matlock Bath and Cromford in the north and almost to the centre of the city of Derby in the south. The industrial settlements which are included are Cromford, Belper, Milford and Darley Abbey. The spine linking the settlements which contain the principal industrial monuments within the site is the river. Historically it was the water power which the Derwent and its tributaries offered that provided the raison d’être for the growth of these settlements. Find out more about how each community developed.

Open each section as pdfs with illustrations here, or scroll down to read.

Building the Communities (pdf)

Richard Arkwright’s Factory Village (pdf)

Housing at Lea Bridge (pdf)

The Strutt Community in Belper (pdf)

The Strutt Industrial Settlement in Belper (pdf)

The River Gardens in Belper (pdf)

Belper Pumping Station and Bessalone Reservoir (pdf)

Milford (pdf)

Darley Abbey (pdf)

Building the Communities

Tentative Steps

The first houses Richard Arkwright built, the North Street terraces of 1776-77, epitomised the essence of what was to become a pattern for the Derwent Valley factory masters. Children were perceived to be an under-utilised resource in society, and with machinery available which was simple to operate they became the workhorses of the factory system.

Once the factory masters had tied themselves to child labour delivered in family units, rather than the apprentice labour favoured by, for example, the Gregs at Styal Mill, they were inexorably committed to house building and to community development. If their mills were to flourish, the families which migrated to the new factory colonies must also flourish, and this meant providing jobs for those members of the workforce who would not find employment at the mill. Many years later a member of the Strutt family declared this to be the hardest part to deliver, and claimed his family’s mills in Belper would have grown larger but for the difficulty in finding adult male employment in and around the town.

In North Street, Richard Arkwright proposed a neat solution. He would offer employment to the wives and children of the weavers who occupied the houses and in the workshops, on the topmost floor, they would weave his yarn into calico. All the Derwent Valley factory masters did much the same. Peter Nightingale could not have been more explicit when he established his own mill and advertised for labour in 1784.

“Weavers, good Calico weavers may be employed and if they have large families, may be accommodated with houses and have employment for their children.”

Nightingale at Lea, in his lead works, and Evans at Darley Abbey with the paper mill, corn mill and other long established water-powered businesses close to the cotton mills, which employed predominantly adult male labour, used these connections to support their cotton mills. The Strutts employed men on their farms and as carriers and in many other capacities, but they also invested in nailshops and framework knitters’ workshops. As early as 1790 the Strutts had built a nailshop in Belper Lane and were still investing in new nailshops in the 1830s.

The weavers Arkwright attracted to Cromford were not limited to those who found a home in North Street. There were others working in the loom shop at the mill; also at the mill there is believed to have been space set aside for framework knitters. Each of these predominantly male occupations played their part in insuring the child labour force was maintained.

The Factory Village takes Shape

After 1789 with the Cromford estate in their own hands, the Arkwrights developed the village skilfully and energetically. The creation of the Market Place gave the settlement a new focus. Traders were attracted to the Saturday market Sir Richard established and were offered inducements to maintain their attendance. At the end of a year prizes such as beds, presses, clocks, chairs etc were awarded to the bakers, butchers etc, who had attended the market most consistently.

In due course the settlement the Arkwrights had planted and nurtured became a viable economic entity. It continued to grow until c.1840. The cotton mills had by then reached their height or even started to contract as the effects of the dispute over the Cromford water supply began to be felt. It is not known how closely the Arkwrights maintained a tie between residence in their cottages in Cromford and work at their mills. As late as 1866 the Strutt rent books imply a close linkage, rent still being deducted from the weekly wages. No similar records survive for Cromford and with the premature decline of Cromford Mill it seems likely that by 1850 some at least of the Cromford housing would have been occupied by families who had no connection with the mills. It is also interesting to note that as early as 1816 half the Cromford Mill workforce of 725 lived outside Cromford and therefore in houses which were not linked to their employer.

Making People do their Best

Even before he took possession of the Cromford estate, Arkwright had established his reputation as an employer who recognised the need for his new community to foster its own identity, social life and tradition. He is credited with the creation of customs in Cromford similar to those which existed elsewhere in older established settlements.

So, in September each year (and certainly by 1776) there was the annual festival of candle lighting when workmen and children, led by a band and a boy working in a weaver’s loom, paraded from the mills round the village. On their return to the mills they received buns, ale, nuts and fruit. In 1778 on such an occasion, a song was performed “in full chorus amongst thousands of spectators from Matlock Bath and the neighbouring Towns”.

As Sylas Neville observed, Arkwright “by his conduct appears to be a man of great understanding and to know the way of making his people do their best. He not only distributes pecuniary rewards but gives distinguishing dresses to the most deserving of both sexes, which excites great emulation”.

The Cromford community was also sustained by the creation of various clubs and friendly societies including a cow club, the the full range and details of this provision is unknown. Information is sparse also for the educational investment in Cromford.

In 1785 a Sunday School was established which immediately attracted 200 children; subsequently there was a day school, the precursor of the school erected in 1832 and which remains open.

The religious life of the community was less well provided for. The chapel built in 1777 on the edge of Matlock Bath by Arkwright’s partner Samuel Need, near the spot which was later to accommodate Masson Mill, was clearly intended for Matlock Bath’s fashionable visitors rather than the mill workforce. In any case, its life was cut short by Need’s death in 1781; and when it did re-open in 1785 it was soon in the hands of an extreme Calvinist sect serving a small congregation.

It was not until 1797, when Richard Arkwright junior opened Cromford Church – which his father had planned as a private chapel for Willersley Castle – that the community’s needs were catered for. The Church was in these early years pressed into service as an adjunct of factory discipline. Unlike the Strutts, the Arkwrights are not known to have encouraged other denominations to establish themselves in their village. The several Methodist sects with their own chapels, which prospered in Cromford in the 19th century were all built on land outside the Arkwright estate.

Richard Arkwright’s Factory Village

Arkwright established his industrial settlement in Cromford over a period of 20 years. The first significant house-building was in 1776 in North Street, followed soon after by the three-storey houses towards the top of Cromford Hill. From 1776 until 1789 Cromford was owned by Peter Nightingale, and it was not until Sir Richard had purchased the estate that the pace of development accelerated. Nor is it possible until that time to discern any element of conscious planning in the community’s development. The village continued to grow under the stewardship of Richard Arkwright junior, and by the time of his death in 1843 it had acquired the size and shape it was to retain until well after the Second World War. It is fortunate that most of the modern housing development in Cromford has taken place in areas which are largely separate from this historic community.

The Market Place

c. 1790

The Market Place provided the heart of Arkwright’s community. It extended right across the road and pavements and included the area to the East. The main bulk of the development within this part of Cromford dates from c.1790. The market which Arkwright started in 1790 was an integral part of his strategy for the development of Cromford and was fundamental to the success of his pioneering achievements. In order to attract the families which were to provide his workforce, it was not enough to supply good housing. It was also necessary to ensure that there was a regular supply of provisions, and this was achieved by attracting traders to the Cromford Market and building the new commercial premises which would retain them.

The Greyhound Hotel, Market Place

1778 – Listed Grade II*

Unambiguously the principal building of the Market Place development, a dignified pedimented, three-storey building, constructed in sandstone with a Roman Doric doorcase and raised quoins.

The Greyhound provided lodging for visitors to Cromford and was used as the location for festivities organised by Sir Richard for his workforce. The Arkwrights also used it for business. It was here in the public room that Richard Arkwright junior instructed Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire to leave her answer as to how she intended to repay the money she owed him.

The Arkwright Stores, 39 Market Place

1780s – Listed Grade II

One of a row of six houses, converted for retail use in the 19th century. Constructed in coursed gritstone with slate roofs. The two bowed shop windows are a rare survival from the early 19th century. Originally it had a slate roof.

The Market Place, nos 2-36

c.1790 – Listed Grade II

A rare example of a single-storey range of Georgian shambles. The range is constructed of regular coursed gritstone with a hipped slate roof. A similar structure once stood in the other corner of the Market Place where the Cromford Community now stands.

Willersley Castle, Willersley Lane

c.1790 – Listed Grade II*

Architect: William Thomas. Interior by Thomas Gardner of Uttoxeter.

A mansion house located on rising ground and set in a Grade II landscaped park. It was commissioned by Sir Richard Arkwright, who died before it was completed. It is constructed of ashlar sandstone. The central facade is defined by projecting turrets. Contemporary observers described Willersley as “an effort of inconvenient ill taste” and “a great cotton mill”. The Arkwright family occupied the castle until after the First World War. In the grounds of the castle the stable block and home farm buildings (though not the farmhouse, which predates the Castle), by Thomas Gardner of Uttoxeter, survive though in an altered form. It is now in the ownership of Christian Guild Holidays.

Read more about Willersley Castle – recent research.

Lodge to Willersley Castle, Willersley Lane

c.1792 – Listed Grade II

Thomas Gardner of Uttoxeter

A picturesque lodge to Willersley Castle. It has an ashlar facade; the remainder is coursed rubble.

The Fishing Lodge, Mill Road

c.1796 – Listed Grade II

A small gritstone structure standing by the ruins of the 15th century bridge chapel and created from an earlier range of farm buildings. The fishing lodge was fashioned by Richard Arkwright junior to function as dwelling for his water bailiff. By the early nineteenth century it was in use as a workman’s cottage. It is a copy of the fishing lodge on the River Dove made famous by Isaac Walton and Charles Cotton. The inscription over the door lintel reads “piscatoribus sacrum” – sacred to fishermen.

Rock House, Mill Road

1776 – Listed Grade II

Built by Peter Nightingale for Richard Arkwright, it became his home during his time in Cromford. It was extended in the 19th century. A three-storey brick and ashlar house constructed on a cliff, it overlooks the Cromford Mills in stark contrast to Willersley Castle which, though constructed in an elevated location, is entirely hidden from the mills and almost entirely from the village. It has been converted to flats.

Read more about Rock House in recent research

North Street

1776 – Listed Grade II*

The first of Sir Richard Arkwright’s workers’ housing in Cromford. The street consists of two long gritstone terraces which face each other across a broad street, comprising 27 dwellings in all. The accommodation is superior to rural housing in Derbyshire at this date and North Street set a pattern for what was to follow elsewhere in Cromford, though it exhibits a higher standard of construction and design than some of the later houses in the community.

The mixture of leaded lights and sashes on two storeys and doorways which echo classical design features, convey a social pretension which would not have been lost on the skilled workers Arkwright sought to attract to Cromford. Sash windows would have been generally reserved for farmers or the commercial classes in this part of Derbyshire at this time. Provision for domestic accommodation was on the ground and first floors with workshop space on the top floor, characterised externally by distinctive ‘weavers’ windows. These workshops enabled members of the family not employed within the mills to earn an income. When these houses were built they were intended for weavers and their families.

Cromford Hill 104, The Hill

c.1780 – Listed Grade II

A three-storey terraced house constructed in coursed gritstone with a tiled roof. This is one of 83 similar dwellings within the settlement. Unlike the earlier houses in North Street, the houses on Cromford Hill provided purely domestic accommodation with no workshop space. The terrace forms part of a long linear arrangement of different housing forms constructed by the Arkwrights on either side of Cromford Hill.

Cromford Hill 122, The Hill

c.1810 – Listed Grade II

Part of the second generation of Cromford industrial housing. These two-storey terraced cottages, two cells deep, were constructed in coursed gritstone with Welsh slate roofs. This is one of 36 similar dwellings within the village.

Cromford Hill, nos. 37 and 39, Victoria Row, The Hill

1839 – Listed Grade II

Pair of houses within a row of eight built for Richard Arkwright junior to accommodate workers in the textile mills. They were constructed in coursed rubble with render and have cast iron windows with opening casements. They are set back behind front gardens which divide them from Cromford’s main thoroughfare, The Hill. The rear elevation has small single-light windows to the upper floors with low lean-to sculleries.

Staffordshire Row, nos. 30-46 Water Lane

Early 19th century – Listed Grade II

A row of three-storey gritstone houses similar in form to those found on The Hill. These are thought to have been constructed for the mill workers even though they may stand on land which was not Arkwright property at the time they were built.

Arkwright’s Houses on Water Lane

Early 19th century – Unlisted

These are three-storey, semi-detatched houses, stone-built and rendered. Six houses follow this pattern; all are on Water Lane. With their substantial gardens, relatively spacious accommodation and privies, they are believed to have been provided for the overseers or foremen in the mill, Cromford’s equivalent of the Darley Abbey and Belper cluster houses – though, of course, they are less innovative in design.

St Mary’s Church, Mill Lane

1797 and 1858 – Listed Grade B

Founded by Sir Richard Arkwright as a private chapel within the grounds of Willersley Castle and opened to public worship by his son in 1797, the church was substantially altered and partly gothicised in 1858. It has an extensive system of mural decorations by Alfred hemming, of 1897, depicting scenes from the Bible. A memorial to Mrs Arkwright (1820) by Chantrey hangs on the north wall of the nave. In the corresponding position on the south wall is a similar plaque dedicated to Charles Arkwright (1850), by Henry Weeks. Sir Richard’s remains were moved from Matlock Church to St Mary’s and interred in a bricked-up vault within the chapel.

School and School House, North Street

1832 and later – Listed Grade II

The school was built by Richard Arkwright junior to provide accommodation for the young mill workers who, under the terms of new legislation, were to be required to work under the ‘half-time system’, whereby part of each day was to be spent at school and part at work. The school was extended in 1893. Both the school and the school house are constructed of gritstone with hipped slate roofs. The School House is accommodated in one of two wings attached to the main building.

The Village Lock-up, Swift’s Hollow

1790 – Listed Grade II

A two-storey three-bay building constructed of coursed gritstone with a graduated Derbyshire slate roof. It was originally built as a terrace of three cottages early in the 18th century, but in 1790 the ground floor of the centre cottage was converted to a village lock-up. The lock-up contains two small cells with metal doors. One cell retains its original bunk, which is suspended from the walls by chain. The lock-up, the adjacent space and the room above have been renovated by the Arkwright Society and the upper floor is now in commercial use.

Privies to the rear of 56-76 Cromford Hill

Listed Grade II

Sandstone privies built in pairs and roofed with monumental gritstone slabs.

Pigcotes, Swift’s Hollow

Late 18th to early 19th century – Listed Grade II

Sandstone pigcotes constructed as part of the Arkwright community development. Pigcotes played an important part in the cottage economy of a village such as this. They are situated amongst allotments, small barns and workshops.

The ‘Bear Pit’

1785 – Listed Grade II

The Bear Pit, as it is known among Cromford residents, was constructed in 1785 by Richard Arkwright. It consists of a more or less oval stone-lined pit sunk into the course of Cromford Sough, a lead mine drainage channel, across which a dam and sluice have been erected. The dam forced the sough water back into a new underground channel which connected the sough to the Greyhound Pond. By this means Richard Arkwright was able to supplement the water stored in the pond with sough water. He used the device each weekend while the mills were not at work so that the Greyhound Pond was adequately supplied when work began again on the Monday morning.

The Greyhound Pond

c. 1785

The principal supply of water for the cotton mills was from Cromford Sough. The first mill was powered exclusively from that source until, from the mid 1780s, it was extended wheel added. This wheel derived its water from the Bonsall Brook via an underground culvert controlled by a sluice in the corner of the Greyhound Pond (adjacent to the present day Boat Inn). It is not easy to date the construction of the Greyhound Pond. It may have been one of the ponds referred to by William Bray in 1783, but he may have had in mind the ponds created on the Bonsall Brook for the corn mill which had been erected in 1780. Certainly, the Greyhound Pond must have been in existence by 1785, when Richard Arkwright incurred the wrath of the lead miners by damming the Cromford Sough at Bear Pit so that he could force the sough water into the Greyhound Pond. The culvert Arkwright built for this purpose can be seen from Water Lane to the rear of the Greyhound coach-house and stable-block.

Former Corn Mill, Water Lane

1780 – Listed Grade II

This water-powered corn mill with its attached cottage was built by George Evans in 1780. It is constructed in coursed rubble and squared block gritstone with ashlar dressings; the cottage has Venetian windows. The kiln adjacent to the corn mill was in existence by 1797. The maltings, now the Cromford Venture Centre, was added in the 19th century. It is interesting to note that the corn mill was constructed within two years of the destruction of the Cromford corn mill to make way for the second cotton mill.

Slinter Cottage, Via Gellia

c.1800 – Listed Grade II

The mill was originally constructed as a lead slag mill associated with a lead smelting enterprise higher up the valley. It was later converted to wood turning and produced bobbins and pulleys for the cotton mills. It is set in an area of great natural beauty dominated by Slinter Tor. The adjacent woodland has been designated an SSSI and an SAC. The structure still retains a small breast-shot wheel with wooden buckets. The cottage has been renovated by the Arkwright Society.

Cromford Station buildings and footbridge

c.1855, 1860, 1874 and 1885 – Listed Grade 11

In 1849 the Manchester, Matlock, Buxton and Midlands Junction Railway opened a line to Rowsley passing through Cromford. The station-master’s house and the up line waiting room were built in c1855 and 1860 in coursed gritstone with slate roofs. The design by G H Stokes bears witness to his work in France with his father-in-law Joseph Paxton in the 1850s. The station buildings on the down line were built in 1874. The Butterley Company erected the ornate footbridge in 1885.

Cromford Bridge Hall (formerly House), Lea Road

17th century with later additions – Listed Grade II

Once known as Senior Field House, it is a 17th century hall and crosswing house with dormer gables – perhaps containing the remains of an earlier building. It is built of coursed gritstone. Some 17th century mullioned windows with transoms survive. In the 18th century wings were added at both ends. The addition at the east end was built in a similar design to the adjacent 17th century crosswing so as to give the overall impression of a symmetrical main front. The main entrance was placed in the middle of this enlarged facade. Most of the windows are sashed and it has a recently repaired stone slate roof. Most of the building is three storeys high. The house was acquired by George Evans, brother and business partner of Thomas Evans, founder of the Darley Abbey Cotton spinning mill, in c1760. It was lived in by his descendants including his daughter Elizabeth Evans, a local amateur artist and great-aunt of the famous Florence Nightingale.

Woodend, Lea Road

1796 – Unlisted

Built by Peter Nightingale, founder of the Lea Cotton Mill, as a replacement for Lea Hall, which he found too cold in the winter months. The house, which is three bays in width and three storeys in height, is built of ashlar gritstone with corner and front door quoins. It has sashed windows with stepped lintels. There are 19th century additions; also a separate coach-house with stabling, which has undergone recent alterations. After Nightingale’s death it was occupied for a time in the 19th century by the Smedley family who took over Lea Mills.

Housing at Lea Bridge

Housing at Lea Bridge: Four cottages adjacent to Smedley’s Mill

1783 – Listed Grade II

Three cottages built to an L-shaped plan were erected in December 1783 at a cost of £110 as part of Peter Nightingale’s cotton mill development. They are strikingly similar to the three-storey cottages built at the same date on the upper slope of Cromford Hill, with mullioned windows on each floor. This row is roofed in Derbyshire stone slate, as the Cromford houses may once have been. A fourth dwelling has been added at a later date with single large windows in each of its two storeys, which spoils the symmetry of the elevation.

Middle Row

1791 – Listed Grade II

A row of six three-storey cottages (originally a row of four, but extended at the upper end of the terrace at an early date), built by Peter Nightingale in 1791 as part of the expansion of his cotton mill enterprise. Like the earlier row which they overlook they have two-light mullioned windows. Each cottage has a massive quoined door surround and plain plank door with a single opening window above. There are some modern renewals. These cottages remain in use as dwellings.

The Strutt Community in Belper

It now requires a conscious effort to distinguish the Strutt settlement from the older Belper community. Over the years the two have coalesced, but in the 1780s they would have been separated by a green no man’s land nearly a quarter of a mile in width. The older settlement, based on agriculture and nailing, had been growing steadily as a market centre even before Jedediah planted his first mill nearby and it is clear that this growth continued alongside, and was further stimulated by the later Strutt investments.

Choosing a community which already had an economic infrastructure meant that the Strutts were spared some of the problems which faced Richard Arkwright in Cromford, a smaller and less developed community. Belper had a market place, public houses, shops and a chapel. From 1801 the town also had a rapidly growing hosiery business established by John Ward and others and later including George Brettle. By c1830 the one business had become two and Belper could claim two of the largest hosiery firms in the country. The hosiers bought yarn from Strutt’s, they also provided further employment in the town in the warehouses and mending rooms so helping to sustain Belper’s accelerating growth.

The Strutt’s land purchases in Belper and Milford followed the same pattern and priority. The first steps were associated with securing land for the mills. In Belper, almost all the purchases between 1777 and 1786 related to the mill and the acquisition of land which controlled the river. The same first steps were taken in Milford where, until 1791, land purchases were concentrated on the immediate area of the mill site and the adjoining meadow.

In Belper, it was not until 1787-88 that Strutt made the crucial purchase which would enable him to build his chapel, later to be known as the Unitarian Chapel, and the houses around it, the Short Rows. By 1801, there were 893 houses (built or being built) in Belper, an increase of 460 over the estimate made by Pilkington in 1789. Thus, in 1801, Strutt owned some 280 houses, or about a third of the total number of houses in Belper. It is clear there were others investing in Belper’s growth apart from the Strutts, just as it is also clear in physical terms that Belper never became truly “Struttsville” – the company town with total ownership of the settlement in the mill owner’s hands, as was the case in Cromford and in Darley Abbey.

During the 1790s the Strutts turned their attention to building up their estate. This was made possible by the Enclosure Award of 1791 which brought with it many opportunities to purchase small parcels of land. Whereas in the first 10 years of development in Belper and Milford Jedediah had bought 48 acres of land, in the following five years, 1786-91, 144 acres were added; and between 1792 and 1796 a further 185 acres. When Jedediah Strutt died in 1797, the estate totalled around 380 acres.

There is no obvious pattern to the Strutts’ house building. The earliest housing, which is thought to be the Short Rows, close to the chapel of 1788, was on the meanest scale, some, if not all, originally containing two cells, on up and one down. This was followed in 1790 by the back-to-backs in Berkin’s Court; but by this time, houses of better quality, three-storey houses, were being erected at Belper Lane.

During the years of 1792-97 the bulk of the three-storey houses in Long Row, Hopping Hill and Smith’s Court were built. Finally, concluding the first phase of house building, the Belper cluster houses were added in 1805.

Of all the surviving examples of this house type, those in Belper most obviously demonstrate the intention to make these houses the first choice for the most important members of the workforce, the overseers. In Belper, unlike Darley Abbey, each had an extension, a substantial garden and an individual lavatory and pigsty.

The documentary evidence which has survived suggests that the tie between working in the mill and residence in a Strutt house was strictly enforced and remained in existence as late as the 1860s. The rent books which include all known Strutt housing, demonstrate how rent was collected through deductions from the wages of the member of the household concerned. The variety of house types in the Strutt housing stock and the range of rents charged to the residents leaves no doubt there was a hierarchy. The best houses, the Clusters or Field Row, could cost 4s 6d per week while at the other end of the scale a house in the Short Rows or Mount Pleasant could be as little as 1s 3d. Smiths Court and Long Row were around 2s 6d. What is not clear is how the houses were allocated. From the tariff it seems unlikely it was arranged on the basis of family size.

A very large business

The size of the workforce in Belper and Milford has been used to suggest that Strutt’s was the largest cotton factory enterprise in the United Kingdom in the early years of the 19th century, but comparisons between the competing claims of the Arkwright empire, New Lanark and the Strutt’s business are difficult. What is certain is the supremacy of the Strutt business within the Derwent Valley.

In 1789, there were judged to be 800 people employed at Cromford and Masson and no more that 600 in Belper and Milford. Yet by 1802, though the Arkwright business had grown to 1,150, the Strutts now employed 1,200 to 1,300, a figure which grew steadily until a plateau was reached around 2,200 in the early 1820s. Subsequently, though there were peaks and troughs, the business maintained this level until at least the 1850s, after which consistent employment information ceases to be available. In Milford, employment reflected a different pattern. Between 1823 and 1837 the number employed in the mill fell from 537 to about 360, and there were corresponding falls among the in-workers, the skilled staff who maintained the machinery. But in March 1824 the foundry and the gas works opened, a year later a dye works; by 1837 this employed over 70 people.

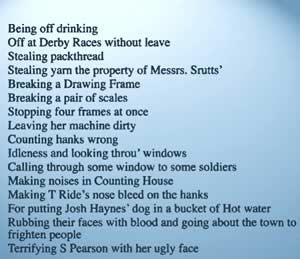

Forfeits had to be paid for inappropriate behaviour, including the incidents recorded above, between 1805 and 1813.

The hours worked in the mills were six before dinner, which was taken between 12 and 1pm, and six after dinner with time allowed within each six hour period for breakfast and tea. The Strutts were quite clear the basic day that had been inherited from the Derby Silk Mill where “this has been the invariable practice… for more than 100 years”. Discipline within the works was maintained by overseers and by a system of fines. Outside working hours, watchmen employed by the Strutts reported anyone whose behaviour became too wayward. In the early days payment was largely in truck and no more than one sixth was in cash. Deductions were made from wages for rent, food stuffs, coal, milk and vegetables. Some of the produce came from part of the Strutt estate, the garden of Bridge Hill House and from Wyver Farm.

Feeding the community

The milk supply was a matter of special concern. The Strutts established a dairy and to see that it received milk throughout the year, they agreed to buy such quantities of milk from suppliers at a price that made it worthwhile keeping cows through the winter, the suppliers paying the Strutts if the supply fell short. Here again, some of the supply was from the Strutts’ own farms at Bridge Hill and Green Hall. The provision of tea and coffee, which began in 1826, attracted attention because of the arrangement whereby any profits were used to pay for medical care required by any of the subscribers. There was also a sick club for all females employed in the mills, which may have been set up as early as 1801 and was certainly in existence by 1821.

By 1821 the Strutts had established the Belper Provision Company, a co-operative enterprise which distributed profits among its customers in proportion to the value of their purchases. A similar society existed in Milford. The arrangements to sell milk continued until April 1854, by which time the scheme had been running for some years at a modest loss. It is not clear whether it was cost or lack of demand which led the Strutts to dismantle this well intentioned strategy.

The Strutts demonstrated their belief in toleration by assisting others to provide places of worship in Belper and Milford. Jedediah’s personal convictions led him to build a chapel in Belper and provide accommodation in Milford for those who shared his Unitarian faith, and the company continued to support the Belper Unitarian chapel financially until at least 1847. But the Strutts were not doctrinaire in their beliefs and actively encouraged other denominations to establish places of worship sometimes contributing financially or by making a gift of land.

Education and Music

The Strutts’ commitment to education embraced Sunday Schools and Day Schools and a number of cultural initiatives which seem far ahead of their time. Before the introduction of the half-time system, the Strutts insisted upon children attending day school before they were offered work in the mills, so guaranteeing a certain level of literacy among their labour force. By 1817, 64 children were attending Day Schools and 650 the Sunday Schools at Belper, while at Milford 300 were in the Lancasterian Sunday School and the numbers grew as the company and facilities expanded. The Strutts insisted on attendance at Sunday School for all their young employees under 20. The cultural life of the community was also taken care of with dancing and meeting rooms made available at the mills and through John Strutt’s band. This was in fact a 40 strong orchestra and choir recruited from work people employed at the mills. They received regular instruction in work time and in return agreed to remain in the Strutts’ employment for at least seven years. The orchestra performed in and around Derby. John Strutt rewarded the members of his orchestra with occasional visits to the opera and to concerts in London.

Like the Arkwrights at Cromford the Strutts were not slow to recognise the value of communal celebrations in fostering social cohesion and loyalty. The events which thrilled Belper and Milford were generally in honour of some great national news. In 1802 it was the treaty of Amiens; in 1814 the declaration of peace; in 1821 the coronation of George IV; but it was the passage of the Reform Bill which produced the most whole-hearted reaction. “The festivities in honour of the reform bill“, the Derby Mercury reported, “have been conducted at Belper on a scale, that we doubt not will equal if not surpass any other in the country. The whole has been arranged by a Committee of Management, aided by the invincible energy of their justly popular towns men, Messrs Strutt.”

The Strutt Industrial Settlement in Belper

Modern Belper represents at least four phases of development: the original medieval rural settlement of Beaurepaire that centres on the chapel of St John; the later growth lower down the hill which, by the middle years of the 18th century included a market place on a lower level than the present one; the industrial community established by Jedediah Strutt in the late 18th century on the northern edge of the existing settlement and around Belper Bridge Foot and up Belper Lane; and the 19th century expansion of the commercial centre along King Street and Bridge Street.

The most prominent of the Strutt industrial housing stands on land to the south of the mill complex and to the east of the Derby-Matlock road. The land was acquired largely through numerous individual purchases, with its end use for workers’ housing clearly in mind. The houses were all of a high standard with gardens and, in certain areas, allotments for the residents. The housing constructed from Derbyshire gritstone or locally made brick, and roofed with Staffordshire blue clay tiles or Welsh slate, was largely placed in an east-west alignment connected by narrow passages giving an almost grid-iron character to the layout. Construction of housing by the Strutt estate continued into the 20th century.

The houses vary in form from row to row as the Strutts experimented with different designs. The result is visually cohesive, attractive and unique mix of workers’ housing.

As well as the land on the slopes to the east of the mills, the Strutts had also by the 1790s acquired land and property and started to build housing on the south facing slope to the north-west, adjoining their Bridge Hill estate. Here, by 1840, they had built or acquired up to 100 houses which were rented to their workforce. The housing in this area was developed plot by plot as land became available. Most of it was built in short terraces of three or four houses, mainly in gritstone, though some are in brick, on levels up the hillside formed by earlier quarrying or along Belper Lane and Wyver Lane. Good examples can be seen in the terraces in the Scotches: in the stepped terraces on the northern side of Belper Lane, culminating in the cluster block which housed the original Belper Parish Workhouse; and in the small groups of houses such as Pump Yard, set back from Belper Lane.

Also of interest is the brick terrace on the southern side of Belper Lane which still retains the arch which was a former entrance to Bridge Hill house. These houses have the appearance of being built for estate rather than for mill workers.

Belper Lane, nos 54-92 (formerly Mount Pleasant)

c.1790 – Listed Grade II nos. 54-56, 58-62, 64-66, 82-84, 86-92

A series of stepped terraces built in stone, some double-fronted and some single, roofed in slate. These houses have large gardens and cellars.

Mount Pleasant Old Workhouse, nos 94-100, Belper Lane

1803 – Unlisted

Back-to-back cluster type houses, stone-built, with a central chimney and three-storey. This was the parish workhouse until replaced by the Union Workhouse, now the Babington Hospital, when it was sold and put to domestic residential use.

Pump Yard Belper Lane, nos 74-80

By 1818 – Unlisted

North side brick stepped terrace in the ownership of the Strutts by 1818.

Pump Yard Belper Lane, nos 68-70

By 1818 – Unlisted

South side. Stone terrace of two, in the ownership of the Strutts by 1818.

Belper Lane, nos 25-33

By 1818 – Unlisted

Five houses in a terrace which was in the ownership of the Strutts by 1818; brick with stone slate roof, of two-storeys and with an archway over the central section, thought to be part of the carriage-way to Bridge Hill House. This feature was restored in 1818-19.

The Scotches, west side Belper Lane, nos 5-8

c. 1819 – Listed Grade II

Four three-storey stone-built houses in a terrace, with a house of two storeys at the western end. By 1844 these houses had associated nailers’ workshops.

Wyver Lane, nos 3, 5 and 7

By 1818 – Listed Grade II

Three (formerly four) terraced houses which were in the ownership of the Strutts by 1818. Of three storeys and stone-built with slate roofs and brick chimneys. Each has an allotment bounded by dry stone walls on the other side of the lane.

Derwent Terrace, nos 6, 7 and 8; also 9 and 10

By 1818 – Unlisted

Stone-built in rubble and coursed stone; purchased by the Strutts sometime after 1818.

Back Wyver Lane

By 1818 – Unlisted

A terrace of four two-storey houses, originally with adjacent nailshops. It was acquired by the Strutts sometime after 1818.

Wyver Lane ‘Weir Lodge Houses’, 39 Wyver Lane

By 1818 – Unlisted

Formerly two, in a stone-built terrace of two storeys and with a large brick chimney stack. In Strutt ownership by 1818.

Short Rows, nos 46 and 47

c1788 – Listed Grade II nos 26-36, 38-47

One of the first groups of houses to be constructed by the Strutts in Belper adjacent to the chapel of 1788. The Short Rows originally comprised four separate rows of largely one-up, one-down cottages containing 47 houses in all. The houses are built in red-brick with slate roofs and brick chimneys.

Mill Street, nos 18-20

c1788 – Listed Grade II nos 2-20

Two rows originally containing 25 houses of two-storey red-brick houses, which originally formed part of the Short Rows (see above).

Former Police Station, Matlock Road

c1848 – Listed Grade II

Located in a prominent position opposite the Strutt Mills, the Police Station was the first of its kind in Derbyshire. The building is constructed in ashlar with a slate-clad hipped roof.

Bridge Foot, nos 18 and 20

c1800 – Listed Grade II

Built as three cottages which were later used as a cottage hospital run by the Strutt family. A long red-brick building with a slate roof.

The Chapel and Chapel Cottage, Field Row

1788 – Listed Grade II*

The Chapel was built by Jedediah Strutt and, apart from the mills, is believed to have been one of the first buildings which he constructed in Belper. Sometime after his arrival in Belper Jedediah adopted the Unitarian faith. The building is a striking example of austere nonconformist architecture built in ashlar with a hipped slate roof. The Chapel was extended on each side early in the 19th century so that in its present form it is three times its original size. The facade to Field Row has a round-arched entrance with a keystone. An external cantilevered stone staircase gives access at first floor level to the gallery. A marble plaque commemorates the life of Jedediah Strutt. The catacomb below the chapel contains the remains of a number of members of the Strutt family including, it is thought, Jedediah himself.

The Chapel cottage which adjoins is thought to have been built soon after the Chapel itself, though the kitchen extension, which is housed in a vaulted space beneath the Chapel, cannot have been constructed until the Chapel was extended early in the 19th century.

Long Row

1792-97 – Listed Grade II

This is industrial housing of a high quality. There were originally 77 houses in the Long Row. It was built in the form of three terraces, two of which were continuous until broken by the North Midland Railway in 1840. The 35 three-storey houses are constructed predominantly in sandstone with a continuous sloping eaves line. They are designed with interlocking plans formed around the staircase.

The southern two-storey terrace is constructed primarily in brick and ascends the rising ground in stepped pairs. Each house has its own garden with allotments behind. There are 62 dwellings in all.

Joseph Street, nos 5 and 6 The Clusters

1805 – Listed Grade II

A plan of August 1805 by James Hicking indicates that it was the intention to build 32 cluster houses in eight blocks of four houses each. In the event only five blocks were built and with some significant variations from the original plan. The plan does not indicate the provision of privies or pigsties, nor is it clear that each block is to have a lean-to outshut at each end.

The houses are designed on the innovative plan first implemented in Darley Abbey of one block divided north-south and east-west to form four back to back houses. Each block is sited in the centre of a large plot and, as they were built, each house has a building in the garden incorporating a privy and a pigsty.

At 7 Joseph Street, the privy and pigcote have survived in a building constructed in coursed stone.

The term ‘Clusters’ was in use by 1820 and the buildings may have borne this name from the outset though this is not clear from Hicking’s plan on which the words have been added by a later hand.

Nailshop Joseph Street, no 8

Early 19th century – Listed Grade II

The nail maker’s workshop, a rare survival, is constructed of coursed stone with a tile roof, brick chimney and cast iron windows. This is a single nailshop; far more typical in Belper were the rows of nailshops, perhaps five or six under a single roof, but no more than two or three of these have survived, all of them altered drastically.

As early as 1790 Strutt had built a nailshop next to one of his cottages. His interest in nailing was solely to provide work for the male members of the families inhabiting his cottages. There is also evidence he invested in framework knitting workshops to achieve the same purpose.

Crown Terrace, nos 4-13 (formerly Smith’s Court)

1794-95 – Listed Grade II

A terrace of three-storey stone houses built by the Strutts for their mill workers. The houses are contructed in pairs on an interlocking pattern in a similar style to the three-storey houses in Long Row. In 1890 the Strutt estate extended the properties to the rear except the two houses nearest to the A6 road.

Field Row, no 6

c. 1788 – Unlisted

Two terraces, 1-7 and 8-13 three red-brick houses standing adjacent to the Strutt Chapel and in marked contrast to the nearby houses in the Short Rows. On the basis of the rent paid these were among the more expensive Strutt properties.

Chevin View, nos 1-10 (formerly Berkin’s Court)

1790 – Listed Grade II

The shells of 10 of these houses had been completed by March 1790. These are an early example of back-to-back housing, a building form of which the Strutts made very limited use. They are of three-stores and built of coursed sandstone with slate and blue tiled roofs. Only nos 9 and 10 have retained their original form. At one time Chevin View contained 18 houses.

George Street, nos 1-12

1840-42 – Unlisted

These two-storey stone and brick-built houses built between 1840 and 1842 were constructed in a single terrace with a roof line and eaves which follow the slope of the ground. They were built on the ground which had previously been set aside for the cluster houses and until George Street acquired its present name in 1899 were known as New Houses, Cluster Buildings. The present stone extensions were added probably in the 1890s.

George Street, nos 13-24

1898 – Unlisted

Some of the later Strutt housing built in Belper. These two-storey brick houses with bay windows and verandas were built on the former Potato Lots (allotments).

Wyver Farm

By 1809 – Listed Grade II

Situated nor the of the town of Belper, the farmstead was built by the Strutt Estate. The farm was in Strutt ownership by 1818, but it is not known when the present buildings were erected.

It demonstrates many of the features for which the Strutt farms are famous: the stone fire-proof construction of the ceilings and floors; the careful arrangement of feed storage for ease of delivery; and the use of natural ingredients allowing feed such as wet grains, cereals of hay to be tipped into pits or carted into stores that open into the first floor mixing room above the cow byres. The cow byres are well ventilated – another Strutt design feature.

The main par of the farm complex comprises an L-shaped group built into the hillside and enclosing a north-west facing yard. The group is constructed of stone with slate roofs. The east and south ranges consist of cow byres with loading bay and hatches opening into the yard and rows of ventilators with iron grilles opening into the cow byres just below the first floor level. Both ranges have arched stone ceilings supporting the stone floor lofts above. Eight feed drops in the south wall serve the cow byres below. At the west end of the range, to the rear, three brick-lined wet grain pits are dug into the slope with doors into the loft where the food was mixed. The western range comprises a stable block with a stone floor and separate feed storage areas.

An east-west range of buildings comprises a wagon lodge, stable and barn. This also is constructed of coursed stone and has a slate roof. The four-bay cart shed has been added to the main range and has a lower roof level supported on four cast iron pillars which have been inserted on massive stone bases.

Other subsidiary buildings include a small stable, free-standing cow-house, hen houses and piggeries.

Crossroads Farm

Post 1818 – Listed Grade II* Farmhouse, Grade II Farm buildings

Crossroads Farm is located on the outskirts of Belper, to the west. It is not shown on a map of 181 and the land was not in Strutt ownership at this date. The design and construction of the farm buildings benefited from the techniques pioneered by William Strutt using cast iron components to achieve a fire-proof structure.

Externally, massive stone outbuildings flank the handsome ashlar farmhouse. The interior has evidence of ironwork within its construction, notably within the kitchen ceiling which is formed of stone slabs fitted into iron beams. The roof of the hay barn incorporates iron trusses and the farm buildings utilise cast iron columns and brick-arched floors.

Dalley Farm

Post 1819 – Listed Grade II* North wing of house and farm buildings

The farmstead lies close to Crossroads and though it was constructed predominantly early in the 19th century it was created from an existing 17th century building. The farm was not in Strutt ownership in 1819. The farm contains numerous features of design and construction which are characteristic of the Strutt model farms: the stone vaulted ceilings and flag floors for fire protection; the systems for moving feed stores to feed mixing; the iron roof supports and the unique range for housing wet grain.

The building complex planned around two yards with an L-shaped group to the north east is for the most part constructed of stone with slate roofs. The L-shaped group consists of a four-bay shelter shed with a flagged floor opening onto a yard. Stone pillars with cushion capitals support the roof. One central pillar supports the ridge. The west-facing range comprises a hay house open to the west and a four-bay hay barn with an open front supported on a pierced shallow-arched iron beam with iron posts dating from 1876.

The north-south range comprises a threshing barn with a wooden threshing floor and straw barn above, a wet grain store with some brick construction and a cow byre with six feeding hatches into the feeding passage. To the north there is a three-storey block under east-west facing gables, containing mixing rooms below and a feed store above.

The ceiling is stone vaulted and the ground and first floors are flagged. Round holes in the floor with metal trap doors allow feed to be dropped through to the mixing room. One of these holes is over a stone mixing trough in the angle between the east-west range of cow-sheds dividing the yard. The roof is supported on semi-circular arches by cruciform-section iron pillars.

The later brick-built wet grain store contains nine feed bins for the storage of wet grains for cattle feed with nine stone-framed pitching holes to the east and west allowing for the delivery of grain and wide, iron-framed, openings onto a passage allowing for shovelling out.

The northern cow-house has stone gables and brick south wall and features a mixture of small original metal windows and later larger ones which cut through the rows of ventilation slits. Iron cruciform-section pillars support the roof of the hay house.

Another cow-house divides the north and south yard and abuts the ashlar carriage entry that links the house to the farm buildings. This carriage entry is of a buff-coloured stone rather than the original pink stone and is a later insertion to increase the status of the building. A further cow-house which forms the east side of the northern yard is built of brick with a walkway supported on brick and stone columns.

Transport Features in Belper

The North Midland Railway, which opened in 1840 on a route between Derby and Leeds surveyed by George and Robert Stephenson, the pioneer railway engineers, passes through the World Heritage Site between Derby and Ambergate. It contains numerous engineering structures of the highest quality which were the work of the Stephensons and their supervising engineer, Frederick Swanwick.

Railway cutting walls

1840 – Listed Grade II (in part)

The route of the railway through Belper was the subject of lengthy negotiation between the Strutts and the North Midland Railway company. The details are obscure, but it would appear that the company’s first proposals were unacceptable to the Strutts and had to be modified. The line was to have been driven through Belper to the west of Bridge Street, crossing under Bridge Street near Crown Terrace and finally leaving Belper close to the school buildings on Long Row. Such a line would have been clearly visible from Bridge Hill House and it may have been this which forced the Stephenson to reconsider their proposals. In the end a line was chosen which kept the railway well to the east of Bridge Street and in a cutting throughout all of its length through the town.

An agreement with the Strutts compelled the company to design each of the bridges carrying the streets severed by the line in such a way as would not alter the existing slope of the street. The result is an impressive man-made “gorge” with sides of rusticated stonework with a stone band carried round from bridges and internal buttresses. Most of the original bridges have survived.

Railway bridges

1840 – Listed Grade II

Spanning the railway along the cutting are a number of fine original bridges. Road bridges span the railway at Field Lane, where the north parapet has been replaced by a metal guard, George Street, Gibfield Lane, Joseph Street, Long Row and William Street. A footbridge spans the railway at Pingle Lane. The construction of the bridges generally comprises an elliptical arch in rusticated rock-faced stone with ashlar copings, impost bands, quoins and voussoirs.

The River Gardens in Belper

Britain, unlike many other countries, is noted for the presence in its towns of parks, gardens, open spaces and recreational grounds. These have played an important role in the lives of millions of people during their leisure time. Such facilities were often created in the 19th century by public-spirited persons. Derbyshire towns are highly representative of this idea, and Belper can boast a significant and prominent recreational site.

The Strutt family were instrumental in developing the idea of public gardens. Long before George Herbert Strutt (1853-1928) developed the River Gardens, his great uncle Joseph Strutt (1765-1844) donated the Arboretum to Derby and promoted its use in the 1840s. Following this, similar schemes started to proliferate throughout Britain, until, in 1906, George Herbert Strutt provided the River Gardens for Belper.

1905: The Belper Boating Association and early developments

By 1905, the Strutt family had sold on their business to the English Sewing Cotton Company. On 15th February, George Herbert Strutt was approached by a deputation wishing him to allow them to use the river above the weir for recreational boating. He agreed, and the Belper Boating Association (BBA) was formed. On 4th April, Strutt granted land for a boathouse and gave boating rights to the association for a three mile stretch north of the mill weir.

The boathouse was built on an island on the east bank of the river, previously used for the growing of osiers (a type of willow tree) to make baskets for use in the mills. The land had previously been known as Pickles Meadow, a name derived from the Middle English word “pichel” meaning “small piece of land”. A landing stage was created and paths made through the osiers. On the east side of the island was the mill lade for the first Strutt mill of 1776, and bridges were used to access the site.

The BBA’s official opening took place in Wakes Week, on 4th July 1905, with George Herbert Strutt performing the opening ceremony for a Grand Water Carnival before 2,500 people. Swimming, boating races, music from Belper United Prize Band and a decorated boat competition followed. Later that month the number of boats for hire was raised to 16.

1905/6: Creating the River Gardens

By the end of the season, £200 profit had been made on boat hire, offsetting the £807 start-up costs of the BBA; but it had become clear to the BBA that the boating events were attracting far more people than they had anticipated. It was agreed the river be dredged, creating a wider pool for boating and a larger land mass for the public to use. It was decided this land would be converted into a formal water gardens, similar to those at Battersea Gardens in London and Belle Vue at Manchester. Additions over the winter of 1905/6 included an improved entrance, new formal paths, landscaping, a platform for use by musicians and a permanent refreshment building. Strutt paid for all this work, also proposing the creation of an arboretum. He saw the project as an opportunity to provide a recreational and educational facility for the town.

During the changes made that winter, a stone wall was discovered 54 inches below the river level. Strutt ordered this be raised and capped with concrete, and the material dredged from the river placed behind it, creating a promenade at the water’s edge. Seats were provided, and rustic arches were created, to be planted with climbing red roses. Between the paths, conifers, hollies, yews, rhododendrons, thorns, cherries, barberries, azaleas and brooms were planted.

The appearance of the original boathouse was heavily criticised by Strutt, who had offered to improve the exterior at his own expense. But the need for a refreshment building and a larger boathouse resulted in a decision to move the boathouse closer to the mills and a tearoom to be placed on the site of the original.

The tearooms were created in the Swiss style by Strutt Estate architects Hunter and Woodhouse, and built by Belper’s Wheeldon Bros. Custom-made, it was T-shaped with black and white timber framed elevations and roof hanging over a front veranda. The roof was thatched with heather to emulate the crofts on Strutt’s Scottish estates. A service area and kitchen at the rear and toilets on either side made for an attraction for those not boating.

A man-made channel, which had provided water to the Strutts South Mill since 1776, ran along the east side of the site, and was transformed into a water garden designed by George Herbert Strutt himself. The channel was dammed to prevent water draining away and a new bridge provided over it to allow an easier route on to the island. Islands were created in the water for plants to grow, and a straight path created along the western side.

When the newly-named River Gardens were officially opened on Easter Monday, 16th April 1906, 6,000 people attended, each paying a shilling entrance fee (or threepence after 5pm).

The success of the boating at this time encouraged George Herbert Strutt to provide an experienced boatman to look after the boats belonging to the BBA and its members. He appointed John MacArthur, who originated from the Isle of Skye and was a capable boatman, to do this work. John MacArthur is the great-great-grandfather of Dame Ellen MacArthur.

1906/7: Growth and improvements

Further landscaping of the River Gardens continued throughout 1906 and early 1907, so that by the start of the new season in 1907, the final layout was in place. Over the 1906/7 winter period, further dredging took place to provide an extra acre of space for visitors, this time using a mechanical dredger. The promenade was widened and supported by deep piles. A dock was created for the mooring of the boats at the northern entrance of the old mill lade.

By the Whitsun fete of 1907, a new walk along the base of the exterior eastern wall had been completed, and named Lion Walk. Rustic fencing was placed along the walk to prevent people falling into the mill lade.

It was decided a fountain and rockwork pool would be an attractive addition to the promenade area, and Pulham and Sons of Broxbourne were appointed to create it. This company also carried out extensive landscaping over the winter of 1906/7, changing the straight path by the mill lade into the winding ‘Serpentine Walk’, adding further planting and adding their speciality artificial rockwork, despite the ready availability of local stone which had already been used the previous year. The artificial stonework was known as ‘Pulhamite’ and frequently mistaken for the real thing.

Also that winter, a new entrance was created from Matlock Road – an arch high above the Gardens from which visitors would have an initial overview of the site before descending by a sloping ramp to a rustic bridge at the southern end of the water channel, which was by then a formal water garden with rockery islands.

Work was also finished on the rustic arches and fences in the central section of the site, and the platform for musicians replaced by a bandstand, again designed by Hunter and Woodhouse, and the wooden section built by Belper’s Wheeldon Bros. The copper roof was provided by Messrs Ewart of London, costing £238.

Changes were made to the Swiss Team Rooms at the close of the first season, as the roof leaked badly and the building was too small to meet demand. It was dismantled and moved nearer the water, the veranda was enlarged and red tiles replaced the heather roof.

A greenhouse was added at the southern end of the site, close to the boathouse, for the growing of bedding plants, and a shelter built for the boatman who issued tickets for boat hire. By this time metal labels had been provided for each plant on the site.

Over 8,000 visitors turned out for the 1907 re-opening on April 1, immediately proving the increase in size for the Swiss Tea Rooms was inadequate.

After 1907: The Final Phase and beyond

The need for a second refreshments centre had been proven, and a pavilion was created over the winter of 1907/08 on a triangle of land at the southern end of the site, surrounded on each side by the water channels to the mills. A metal footbridge was created by Andrew Handyside and Co for £339 to provide access.

The following winter, the Matlock Road wall running along the eastern edge of the site was heightened by nearly two feet to discourage people from climbing the wall to see the gardens and entertainments without payment. The Belper Boating Association Committee insisted this was as much for safety reasons as forcing people to pay an entrance fee. The higher wall replaced canvas screens used in 1907 and 1908 to block the view.

In 1911 changes had to be made to the pavilion, removing the southern tip so that the new East Mill could be built beside it. The pavilion was extended on its eastern side to recompense, with the provision of an open veranda.

During the First World War, the gardens were adapted for use as allotments. As the war entered a fourth year, the Belper Boating Association was forced to dissolve. George Herbert Strutt decided to give the River Gardens to the English Sewing Cotton Company (ESCC), and a deed of conveyance was signed in March 1918, although full managerial control wasn’t implemented until 1923.

The Gardens continued to be used for entertainment after the war, and turnstiles were erected for entrance at the southern tip of the site in the 1920s.

In 1955, the ESCC offered the Gardens to the Belper Urban District Council, but their offer was declined. They tried again in 1961, and received the same refusal. Only after the demolition of the pavilion in 1965 and the provision of a new landing stage did the council finally agree to take on ownership in 1966. It was at this time the Swiss Tea Rooms were closed.

The change of ownership finally saw the penny entrance fee abolished. In 1970, the council decided to fill in the northern end of the mill lade to provide a children’s playground. Ownership changed again with local government re-organisation in 1974, and the formation of Amber Valley District Council, who have cared for the River Gardens ever since. Interest in the gardens has steadily increase, with a 15-seater pleasure boat offering rides from 1992, and the town’s well-dressing festival being based in the gardens from 1997.

Milford

Milford to the East of the River

The Strutts started purchasing land in Milford in March 1781 and immediately began to construct the first structure in what was to become a complex of cotton mills and bleach works. At this point along its course the river had long been put to use to provide the power for industrial processes and Strutt’s first acquisitions were two of these sites, the New Mills and the Makeney Forges and the Hopping Hill Meadow which included a fulling mill. Some cottages came with these properties and there would have been some local labour available but it cannot have been long before there was a demand for more accommodation to house an expanding workforce. In Milford, in addition to the houses the Strutts built, further mill workers’ housing was built by local people responding to the economic opportunities the Strutts created.

On the east side of the river the land rises steeply, and the Strutts had little alternative but to construct their cottages in terraces which follow the natural contour and run parallel to the road and the river. On the west side, a less severe slope enabled the community to develop along more flexible lines although the housing here also followed the existing road pattern.

The actual layout is likely to have been determined more by the availability of building plots than by the convenience of the location or by planned development. In 1791, the Enclosure Award brought to the market much land in Milford and the Strutts were well placed to seize this opportunity.

The houses and farms which formed the Milford factory settlement have survived substantially intact with little demolition, though some of the houses have been altered unsympathetically. By contrast, the industrial sites which were for so long the economic hub of the community have been reduced by the clearance of c.1960 to a handful of later buildings and a range of archaeological features. On the former cotton mill site, two wheelpits remain, together with the base plates of William Strutt’s suspension bridge of 1826 which was removed in 1946. Only the foundry the Strutts established c.1825, on Hopping Mill Meadow, has continued in use in the ownership of Hepworth Heating. To the south of the former cotton mill site, the Strutts’ flour mill built on the Makeney Forge site to replace the Duke’s corn mill which they had demolished, remains.

The list which follows is a selection rather than a comprehensive inventory of the places of worship, public houses, farms and cottages constructed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Foundry Lane, Derby Road, nos 2 and 3

c.1818 in present form – Listed Grade II

A pair of semi-detached houses constructed from, or on the site of, an earlier farm which was purchased by the Strutts in 1818. They are of coursed stone with a tiled roof with off-centre chimneys and of two storeys. The ground floor windows are of iron set in wooden frames with some opening casements, with smaller iron windows above.

Duke’s Buildings

1822-23 – Listed Grade II

Numbers 2 to 8 Duke’s Buildings, Derby Road were built on land the Strutts purchased in 1818 from the Duke of Devonshire, hence the name. They were built between 1822 and 1823 at a cost of £466 and are of three storeys in coursed stone with brick chimneys, but most of the roofs have been replaced. Number 2 forms part of an interlocking house plan with number 65 Hopping Hill (West Side). It also has a fire-proof ‘pot’ floor in the third storey.

Hopping Hill, (East and West) Terrace, nos 1-26

1818-20 – Listed Grade II

This back-to-back terrace was built by the Strutts between 1818 and 1820. The terrace is built into a steep hill side. The east side (nine double-fronted houses) is of two storeys. On the west side (14 houses) the houses are of three storeys. They are built of coursed stone with slate roofs and brick chimneys.

In an ingenious interlocking plan the cellars of every other house on each side are dug into the hill side. Some iron casements and sash windows survive. The approach to this terrace can be made by a substantial stone staircase flanked by enormous coursed stone walls and iron posts. Each house also had a garden plot divided again by substantial stone walls and steps. Some small stone-built sheds survive in the gardens: probably, originally, earth closet lavatories. At the north end of the terrace a wide stone paved embanked chute from the road enabled carts to tip their loads into the yard.

Hopping Hill (North East side), nos 1-30 and 31-52

1792-97 – Listed Grade II

This early industrial housing was built between 1792 and 1797 on land Jedediah Strutt received from the Enclosure of the common land and by purchase from Tristram Revell. There are two separate terraces of 28 and 29 houses. Both are built of coursed stone with a stepped roofline. They have slate roofs and brick chimneys. All are of three storeys, although numbers 2-7 have small gabled attic dormers. Each has one window on each floor at the front and casements at the rear. The first floor windows vary between casements and smaller sashes at the front and rear.

There are casements on the second floor. These are said to be Strutt designed and are nine-paned iron windows, four panes of which form each casement. It is clear that though they are of an early date they are not original. The first floor windows have voussoirs. Some modern alteration has taken place to the windows. On the rear elevation evidence survives of an original exit to the garden at half-landing level by means of a bridge. Number 28 is double-fronted and shaped to accommodate the road which ran between it and number 29 which once housed the Milford Provision Company, the Strutts’ Co-operative. The manager lived on the premises and his assistant next door at number 30. On the present garage site was a warehouse, stable and slaughterhouse.

Hopping Hill (South West side), nos 57-65 (consecutive)

Early nineteenth century – Listed Grade II

These houses were built in the early 19th century by the Strutts on land purchased in 1791. They are built in coursed stone with brick chimneys and two storeys high, though number 58 has three storeys with the same roofline. Numbers 61 to 64 (consecutive) have dormers. A stockinger’s shop survives at the rear of number 64.

Houses around the east side of the bridge

1792-1859 – Listed Grade II

This cluster of buildings, some of which have been restored recently, were built between 1792 and 1859 by speculators building on an enclosure allotment taking advantage of the economic opportunity created by the Strutts’ investment in Milford.

Housing at Makeney

Forge Cottage, Makeney Road

c.1830 – Listed Grade II

It was built c.1830 on the site of any earlier building, near the site of Makeney Forge. A coursed stone house, it has modern stone eaves and a slate roof, cast iron adjustable gutter brackets and cast iron casement windows set in wooden frames. It was purchased by the Strutts in 1855.

Forge Hill, Makeney Road

1791 – Unlisted

Originally a double-fronted house which was built by Samuel Crofts on an enclosure allotment. A shop was subsequently added. The building was purchased by Anthony Radford Strutt in 1819 and converted to three houses.

Forge Hill Place, Makeney

1791 – Unlisted

A double-fronted house originally with a stockinger’s shop on the north side built by Zephaniah Brown and subsequently converted to three houses. Two further small houses were added on the south side in 1823 by Z Brown junior. These houses were purchased by Anthony Radford Strutt in 1836 for £280. A pump stands nearby.

Forge Steps, nos 1-5 (consecutive), Makeney Road

c.1750 – Unlisted

Built of small bricks as a terrace c.1750 by the ironmaster Walter Mather for his workers. The doorways are shallow arched and the windows have sashes of a later date.

Makeney Yard, nos 1-4 (consecutive), Makeney Road, formerly Johnson’s Buildings

Eighteenth century – Listed Grade II

This block was originally a farm of considerable antiquity (possibly 15th century) and stabling. It is built of sandstone ashlar with an old tiled roof. It was partially rebuilt in 1732 after a fire. The Strutts purchased it in 1806 and converted it into three or four houses.

Makeney Terrace, nos 1-8 (consecutive), Makeney Road

c.1820 – Listed Grade II

This was built by the Strutts as a terrace of back-to-back stone houses. It has a hipped slate roof with moulded stone eaves and is two storeys in height.

Derby Road, Mount Pleasant, nos 1 and 2

1672 with later additions – Listed Grade II

Dated 1672 double-fronted, of coursed stone with mullioned windows most of which have been replaced by 19th century mullions.

Derby Road, Milford House

c.1792 – Listed Grade II

A large ashlar stone house standing on embanked grounds built for Jedediah Strutt, who lived here briefly before moving to Derby. The main elevation facing east is of a symmetrical design. The building is two storeys high and has a slate roof and sash windows. The central round-arched doorway has an entablature with pilasters.

Derby Road, Moscow Cottages

By 1829 – Listed Grade II

These were built as one building in the early nineteenth century, but in a 17th century style, to house farm workers.

Sunny Hill no 4

c.1813 – Listed Grade II

The former ‘Royal Oak’ public house was built in the early 19th century of three storeys in coursed stone with brick chimneys and with later tiled roof and a symmetrical facade. Anthony Radford Strutt purchased it in 1847. It has ‘Strutt’ adjustable iron gutter brackets and cast iron windows within timber frames.

Sunny Hill, nos 7 and 9

c.1792 – Listed Grade II

These two-storey houses were built by Henry Reeder c.1792 and sold to the Strutts in 1808.

Sunny Hill, nos 13-37, formerly Sunny Hill Place

c.1791, 1807-22, 1823-24 – Unlisted

Tradition has it that this building served as a barracks – a residence for unmarried workers living away from home. It is of brick construction on the west side but stone on the east. The lower side is of three storeys and the upper of two. It was begun in 1791 when a single house was built by Thomas Sims. A further 11 houses were added between 1807 and 1822 by John Farnsworth and four more in 1823-24. Anthony Radford Strutt purchased this property in 1831 to accommodate small families.

Sunny Hill, no 45

1807 – Unlisted

Built by John Bates for Edward Marson and purchased by the Strutts in 1856.

Sunny Hill, no 47

1808 – Listed Grade II

A two-storey double-pile stone house, gable end onto the road, built as a house and shop by John Bates for William Cash, a joiner. It was purchased by the Strutts in 1856.

Chevin Alley, nos 1-5 (consecutive)

c.1792 – Listed Grade 11

Strutt’s terrace built c.1792 is an early example of sloping roof construction of three storeys in coursed stone, with slate roof and brick chimneys. Each house has a single room on each floor lit by a single window. Number 1 adjoins the mill buildings and the extension to the front was added in the 20th century for the village post office.

Chevin Road, nos 7-17, and 2 Sunny Hill (formerly Hazelwood Place)

1791-1816 – Listed Grade II

12 dwellings built by William Marriott in 1791 which included butcher’s, baker’s and stockinger’s shops and a public house. Purchased by Anthony Radford Strutt in 1833 for £1,320, the Strutts later converted the public house into a reading room for the use of Milford residents.

Well Lane, nos 8-14 (consecutive)

1792-96 – Listed Grade II

A two-storey terrace in coursed stone built by the Strutts between 1792 and 1796. It has a hipped slate roof in diminishing courses, brick chimneys and sash windows. The stone wall on the eastern side of the street contains a recess for a pump. Cast iron launders were fitted to these houses in 1820.

Chevin Road, nos 4 and 6, once known as ‘The Bleach Houses’

1792-1796 – Listed Grade II

Originally a row of eight built for the bleach mill management by the Strutts. They are of two and a half storeys in height with brick chimneys. They are seen at their best from across the valley. This elevation reveals their superior status.

Chevin Road, Banks Buildings, nos 1-16 (formerly called Bank Buildings)

1792-96 and 1911 – Unlisted

A terrace of two storey houses in coursed stone built by the Strutts between 1792 and 1796. The terrace was demolished three houses at a time and rebuilt as double-fronted houses with entries in 1911.

Chevin Road, Banks Buildings, formerly Bank Buildings, nos 18-21 (consecutive)

c. 1820 – Unlisted

A stone built terrace, c.1820, built by the Strutts.

Derby Road, Moscow Farm

1812-15 – Listed Grade II*

The farm was built by the Strutt family to supply produce to their workforce. The large, planned steading, largely constructed in gritstone with Welsh slate or Staffordshire plain tiled roofs, is enclosed by perimeter walls.

The principal original building consists of a T-shaped two-storey block that included a stable, cart sheds, feed preparation area and first floor storage. Two attached cow-houses form single-storey wings. On the south side of the cow-house was a large fold yard; a second large yard is enclosed to the north of the T-shaped block, which incorporates two forms of fire-proof construction. The first floor is carried on brick jack-arches springing from iron skewback beams – a form of floor construction paralleled in contemporary mills and warehouses built by the Strutts, and the first floor ceiling consisting of groined brick vaults without structural iron. Shortly after constructing the steading an L-shaped extension to the east cow-house and a linear extension to the west cow-house were added in the same style.