History & Development

History and Development

Not only was textile production revolutionised with dramatic consequences for the British economy, the Arkwright model also informed and inspired developments in other industries. It was here in the Derwent Valley that the essential ingredients of factory production were successfully combined. A source of power, in this case water power, was applied to a series of complex mechanised processes for the first time on a relatively large scale.

Our Inheritance

Our inheritance from the Derwent factory masters, Richard Arkwright, Jedidiah Strutt, Peter Nightingale and Thomas Evans, also includes some of the first examples of factory housing and of industrial communities.

These are not model villages in the sense that they were pre-planned or built to a known blue-print but they soon became models for other community builders within Great Britain and abroad. Within these social units the factory master (later it would be more accurate to use the word squire) was almost as much in control of the residents in their homes as he was of his workforce in the mills.

The social controls which are most obvious in Belper, the tied houses, the fines for misbehaviour at work and in the street, the watchmen, the payments in truck and the more subtle influences associated with food and welfare provision, were no doubt in use in Cromford and Darley Abbey in a similar if not identical form. But the documentary evidence of life in these communities has not survived to the degree it has for Belper and Milford.

What other factors should be taken into account?

For Lombe, recent research suggests Derby’s leading citizens wanted the silk mill established there. It is known that Arkwright sought a reliable source of water but he was also attracted by the easy availability of child labour in and around Cromford, where the lead mining industry offered little scope for the employment of young children. He also needed to be near the hosiery centres of Derby and Nottingham where he expected to sell his yarn.

This market horizon was also the boundary within which Arkwright’s financial sponsors – Samuel Need from Nottingham and Jedidiah Strutt from Derby – were prepared to operate.

The problem they sought to resolve was widely recognised. Demand for yarn had outstripped supply and while Hargreaves’ Jenny offered a significant increase in output over hand-spinning, it was a relatively complicated machine to operate and not suitable for child labour. The Arkwright frame and the family of devices which followed it were, in contrast, all of a scale and simplicity of operation as to be suitable for young people.

Sir Richard did not achieve all his objectives. Some processes eluded even his mechanical skill. He had to persevere with hand picking and cleaning his raw cotton: the devices he had patented for this purpose did not work. But even where hands had to replace machines in the Arkwright system, he ensured the smooth delivery from one process to the next. Stanley Chapman sees this as the essence of Arkwright’s achievement: “The novel requirement was co-ordinating and managerial skill rather than the traditional artisan technology”. Once the Arkwright system had been established it was the absence or scarcity of such skills which as much as any other factor determined the rate at which the system was disseminated. Those who mastered the new spinning system found they possessed skills which were much in demand. It was through these custodians of the new technology that the Arkwright system was propagated at home and abroad.

By 1782-84 it was clear that Arkwright’s patents were at risk, and after 1785, all restrictions had been set aside. Investment opportunities in the new industry, which had been confined to Arkwright, his partners and his licensees (and some who operated outside the law), now became available to a wide spectrum of investors, opportunists and would-be entrepreneurs. By 1788, Chapman’s figures suggest no less than 208 Arkwright-type mills were in existence in Great Britain and there were four mills in France and five in Germany. There were also a number of mills in Ireland. Already the development which had begun so tentatively in Cromford in 1771 had instigated widespread cultural and economic change.

Why the Derwent Valley?

Why these developments should have happened in the Derwent Valley, rather than in any one of numerous locations endowed by nature with a reasonable water supply, is a question to which there may be no single answer.

The natural potential of the river Derwent, at first sight a powerful element in the story, is on closer examination less a determining influence in the first steps of this chain of events than might be anticipated. The water power requirements of the early initiatives in Derby and in Cromford were so small, a large source of water power would have been an embarrassment. So in Derby, Lombe used the town corn mill weir and leats; and in Cromford, Arkwright positioned his first mill on a lead mine drainage channel and a modest brook. The later developments in Belper, Milford and Darley Abbey and at Masson Mill, were on a larger scale: by this time, it was worth investing substantially in the engineering solutions required to tame the volatility of the river and so enjoy the massive power it could provide.

The Significance of the Derwent Valley Mills

It was Richard Arkwright’s Cromford Mill which provided the true blueprint for factory production. Arkwright’s system was copied widely in many parts of Britain and, soon after, in other countries.

The structures which housed the new industry and its workforce and the landscape created around them remain. Overall, the degree to which early mill sites in the nominated area have survived is remarkable. The value of Cromford in the nominated World Heritage Site is further enhanced by the survival of the settlement that was constructed contemporaneously with the industrial buildings to accommodate the mill workers. Cromford was relatively remote and sparsely populated, and Arkwright could only obtain the young people he required for his labour force if he provided houses for their parents. In Cromford, there emerged a new kind of industrial community which was copied and developed in the other Derwent Valley settlements.

Arkwright’s activities stimulated a surge of industrial growth in the Derwent Valley. His close association with the entrepreneurs Jedidiah Strutt, Thomas Evans, and Peter Nightingale set in train a series of important developments between Cromford and Derby. All were successful industrialists, whose economic interests extended well beyond cotton manufacturing. They were also enlightened employers who displayed a strong sense of responsibility for their workforce, their dependants and for the communities that came into being to serve the new industrial system. As such, the developments at Belper, beginning in 1776-77, at Milford in 1781 and Darley Abbey from 1782, provided early models for the creation of industrial communities.

Today, the housing and infrastructure in these settlements, which were brought into being by the same economic and industrial pressures and constraints as Cromford, offer unique opportunities for comparison and analysis. In each case, there has been a high degree of survival and the number of houses of an early date, the range of the house types and the extent of the community infrastructure, are the components of an archive of bricks and mortar of unparalleled importance. Nowhere outside the Derwent Valley does the physical evidence of the early factory community survive in such abundance.

Early cotton mills were so profitable, entrepreneurs were prepared to risk prosecution for infringing Arkwright’s patents to obtain a share of the market. By the time the patents were finally set aside in 1785, a ‘gold rush’ was in progress. This continued until boom turned to bust but by 1788 over 200 Arkwright type mills had been established in Great Britain.

The Inventions

The Arkwright Inventions

The development of the Arkwright water frame made available the first continuous spinning process which could be operated by machine minders rather than skilled operatives.

Arkwright’s first patent, which he obtained in July 1769, was for a machine which spun yarn by means of rollers, flyers and bobbins. The cotton was “drawn” by pairs of rollers, each successive pair moving faster than the preceding one, with twist added by bobbins and flyers. The front pair of rollers was weighted by lead weights hooked over the top roller. This prevented the twist running back up the roving and forcing the rollers apart. The top roller was covered with leather and the bottom one fluted so that the cotton was held firmly as it passed between the two.

The production models used the basic drafting head shown in the patent drawing mounted side by side on a wooden frame and driven from a water wheel by gearing, wooden line shafting and belts.

Joseph Wright’s portrait of Sir Richard shows his subject and, by his side, the invention on which his fame and fortune were based. In selecting the drafting head (the roller device), as the icon of his subject’s achievement, and in painting it so accurately, Joseph Wright demonstrated a genuine understanding of the Arkwright spinning process.

The production models of the water frame varied in size from four spindles to the ninety-six spindle machine, an example of which, from Cromford Mill, is preserved at the Helmshore Higher Mill Museum in Lancashire. The factory masters found it an advantage to have frames of more than one size so that they could produce yarns in varying degrees of thickness, known in the trade as counts, in appropriate quantities according to the demands of the market.

Arkwright’s Second Patent

Some of the Elements of Arkwright’s Second Patent 1775

Once Arkwright had successfully adapted his spinning machine to factory production, he turned his attention to the preparatory processes which precede spinning in the production of yarn. The need had become acute. Until carding and roving could be mechanised to keep pace with spinning, continuous production, the essence of the factory system, could not be achieved. Arkwright’s solutions to these problems were set out in his second patent which he obtained in 1775. This comprised a series of devices with which he addressed the technical problems of opening and cleaning the cotton; carding, a process by which all the fibres are laid parallel; and the creation of slivers and rovings, the loose, slightly twisted ropes of fibre which formed the raw material for the spinning frames.

By no means all Arkwright’s solutions were effective. His attempts to mechanise opening and cleaning failed and these, the first stages in making ready the raw cotton, continued to be performed by hand until the 1790s when the first successful batting machines became available.

Overall his achievement was remarkable, both in its immediate affect and in its longevity. Some of Arkwright’s inventions such as the crank and comb continued in use on carding machinery until the middle of the twentieth century. The Arkwright system, or “package” of processes has been, and remains, of the greatest significance to the world’s textile industries. The improvements that Arkwright made to carding were ultimately applied to all textile fibres other than monofilaments and the modern machine is a recognisable descendent of Arkwright’s first factory models.

Roller drawing, too, had a wider application and was adapted to deal with other fibres. It remained a key component of the mule, of the throstle and of the ring frame, the most important devices by far in the spinning of cotton, wool, flax, jute and waste silk, as well as of chopped synthetic fibres.

The international implications of Arkwright’s inventions were wide-spread and extended beyond the immediate economic effects of technological transfer as the Arkwright system became established in countries outside Great Britain. The factory production of cotton yarn also led to cotton becoming the most important textile fibre in the world for a period of more than a century and the impact of large scale cultivation on countries such as the United States, Egypt and India was profound.

The Arkwright system made possible the production of cheap clothing and household textiles for a wide cross-section of the population, improving comfort and personal hygiene.

New Technology Crosses the Sea

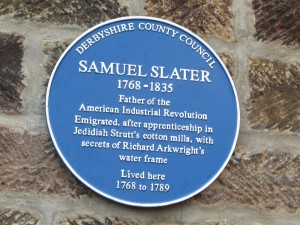

The dissemination of Arkwright’s factory system overseas was achieved partly by the migration of skilled workmen and sometimes by piracy. Samuel Slater, 1768-1835, who had served his apprenticeship with the Strutts in Milford, and who migrated to the United States, is the prime example.

In Europe, industrial piracy played a more significant part. In Germany, Johann Gottfried Brugelmann was the pioneer. His access to the Arkwright technology was achieved through a third party who persuaded a number of Arkwright’s work people from Cromford and Nottingham to move to Ratingen. As early as 1788, according to Dr S D Chapman there were four Arkwright type mills in France and five in Germany.