Global Cotton Connections

Global Cotton Connections: The Derwent Valley Mills

Sourcing the Cotton – Global Impacts of the Cotton Trade

In recent years members of the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site Partnership have been researching the wider international links of the DVMWHS story, in line with UNESCO’s aspirations for the Site. This has involved investigating the sources for the raw cotton (and silk, to an extent), which fed the ferocious appetite of the mills along the valley and elsewhere.

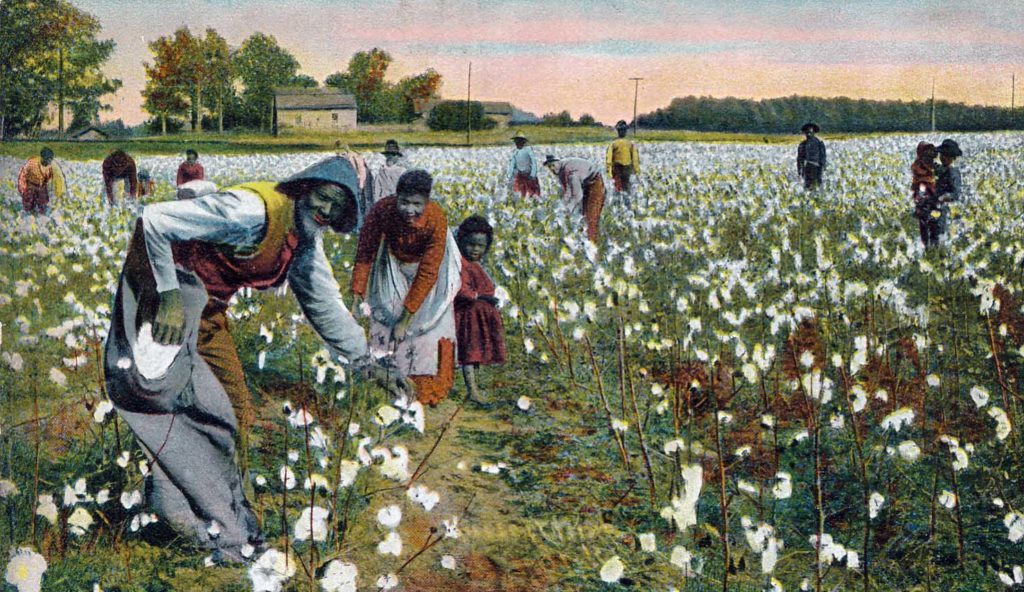

Much of the raw cotton was produced by enslaved people in the Americas. The industrialisation of Britain and the greater productivity of the factory system, which began in the Derwent Valley, led to unprecedented demands for cotton which contributed to an inhuman and brutal regime of historic global slavery.

Work is on-going to examine, discuss and communicate these histories and their legacies more widely.

The Global Cotton Connections Projects

The Global Cotton Connections (GCC) projects began in 2014 through a collaboration between university academics and community organisations and volunteers of diverse heritage backgrounds, with support from the DVMWHS.

They set out to address a gap in historical understanding and public communication of the global connections of the Derwent Valley’s cotton industry, particularly those related to colonialism and slavery, through active engagement with local community groups of African and South Asian descent.

The collaboration built on earlier and parallel work by the Sheffield Hindu Samaj heritage group (see http://heritagehundusamaj.wordpress.com) and the Nottingham-based Slave Trade Legacies group (renamed Legacy Makers in 2019) facilitated by Bright Ideas Nottingham (see https://slavetradelegacies.wordpress.com/projects/global-cotton-connections/). The Global Cotton Connections projects have involved historical research on the Derwent Valley Cotton firms, particularly those owned by the Strutt and (in process) the Evans family, and interpretation of cotton’s global connections through community-led heritage materials. These include key contributions to the DVMWHS Visitor Centre at Cromford Mills and special public events. The work has been supported by funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council’s Connected Communities programme and the Heritage Lottery Fund (now the National Lottery Heritage Fund), the DVMWHS and The Arkwright Society.

The first project in 2014-15 produced historical research on the Strutts (Seymour et al, 2015), and community-led heritage materials, including the Slave Trade Legacies group’s Global Cotton Connections film (2015) and the Sheffield Hindu Samaj’s poetry collection, British Raj in the Peak District: Threads of Connection (see https://globalcottonconnections.wordpress.com/).

This work informed the first phase development of the DVMWHS Visitor Centre at Cromford Mills which opened in 2016. The Global Cotton Connections team provided maps showing the origins of raw cotton used by the Strutts in the Derwent Valley, information on global cotton connections to transatlantic slavery and cotton textile production in the Indian subcontinent, and the design for the award-winning Global Cotton Workers mural produced by Brian Gallagher.

The first project achievements were shared through an Arts and Humanities Research Council Connected Communities Festival event in June 2015, hosted at Cromford Mills and Belper North Mill. Team members also contributed to the DVMWHS 2016 Research Strategy.

The second project in 2017-2018 focused on further development of community-led heritage materials and the interpretation of the cotton industry’s global cotton connections for the second phase development of the DVMWHS Visitor Centre at Cromford Mills, in collaboration with The Arkwright Society.

Opened in 2018, the Centre now includes interpretation of the award-winning Global Cotton Workers mural and a new community-led panel with sections on Ancestors’ Voices from the Nottingham Slave Trade Legacies group (see https://ancestorsvoices.home.blog/derwent-valley-mills/) and Spinning A Yarn, Weaving a Story from Sheffield South Asian groups. An audio station, Global Cotton Connections Voices, allows visitors to hear recordings of commemorative poetry and song, accounts of enslaved life on cotton plantations and reflections on the importance of the project to the community, heritage and academic partners.

The current Legacy Makers project (2019-2021) led by Brlght Ideas Nottingham, is focused on the cotton business of the Evans family at Darley Abbey (see https://legacymakers.home.blog/) and involves volunteers drawn from both the African Caribbean community and wider communities in the Darley Abbey area. It is undertaking historical research on raw cotton supplies and textile products, and enslaved and mill workers, which is informing a range of interpretative heritage materials.

In October 2019 the Legacy Makers project facilitated the first Black History Discovery Day at Cromford Mills, with a range of activities including a gospel performance focussed on the history of cotton and enslavement.. This was a collaboration between community members and academics.

Legacy Makers a compelling journey through time, heritage and empowerment

This film provides an opportunity for audiences to reflect on the ongoing, creative and transformative process that is the Legacy Makers’ journey. A compelling documentary chronicling the inspiring odyssey of local researchers from Nottingham’s vibrant Black communities. Immerse yourself in a unique cinematic experience, skilfully woven with carefully curated clips, photos and footage, as we explore the Derwent Valley Mills World Heritage Site particularly Darley Abbey Mills and St Matthews Church.

The Derwent Valley Mills and Transatlantic Slavery: What we know so far

In the later 18th and early 19th centuries the Derwent Valley was a leading site in the industrialisation of cotton textile production in Britain. The main cotton mill owners all drew heavily on supplies of raw cotton produced by enslaved African people in the Americas. This was the mainstream practice across the country.

Varieties of cotton from the Americas included the longer or stronger staple quality favoured in early mechanised spinning processes. From the 1810s enhanced technology made it possible to mix shorter staple or lower quality cotton with long staple varieties and still produce high quality yarn (Pereira 2018).

In the period 1770-1800 West Indian raw cotton supplies were the most important sources nationally, with secondary amounts coming from Anatolia (modern Turkey) and the Levant (modern Syria and Lebanon) during the 1770s and Brazil in the 1780s (Pereira 2018). Cotton from the southern states of America grew in importance from the 1790s with supplies from Brazil, other parts of mainland South America and the West Indies of continued significance.

While Brazilian and other South American cotton supplies remained important in the early decades of the 19th century, West Indian sources declined and cotton from the southern states grew to dominate the British raw cotton market in the 1820s to 1860s (Riello 2013). These raw cotton supplies, except those from Turkey and the Levant, were all from areas dominated by production systems worked by enslaved African labour and were vital to the Derwent Valley cotton mill businesses.

None of the Derwent Valley Mill owners appear to have been direct investors in the slave trade, proprietors of plantations or enslaved African people, or recipients of compensation for enslaved African people when slavery was abolished in the British Caribbean colonies in 1834 (Seymour et al 2015). However, they traded regularly in raw cotton with those who were slave traders and plantation owners, including the largest and most prominent pro-slavery firms of John Bolton, the Tarletons and the Earles based in Liverpool (Seymour 2018) and the Strutts also had family connections through marriage with people involved with the African slave trade.

Yet there is evidence that the Derwent Valley mill owners and members of their wider families had abolitionist sympathies in respect to both abolition of the British slave trade and slavery itself. They also traded and socialised with known abolitionists, invested in the Sierra Leone Company, a colonial settlement and trading venture led by prominent Christian abolitionists, and on occasion petitioned against slavery in parliament.

Despite this there is no clear evidence that the Derwent Valley Mill owners made sustained attempts to source raw cotton from free labour sources.

The Arkwrights of Cromford

While the Arkwrights, particularly Sir Richard Arkwright (1732-1792), are the best known of the Derwent Valley cotton mill owners there is limited surviving publicly available archival evidence of their activities in the Valley.

We do know though that the firm had an account with Nicholas Waterhouse, the leading Liverpool cotton broker, in the 1790s to early 1800s (Fitton 1989; Krichtal 2013). A rare surviving account shows Richard Arkwright junior (1755-1843) buying large amounts of raw cotton via Waterhouse in 1799-1801 and around half of this was supplied by known slave traders or plantation owners.

A particularly important supplier to Arkwright was leading Liverpool merchant, John Bolton, a large scale slave trader and plantation owner, who sourced cotton from Guyana, the West Indies and the southern states of America (Seymour 2018; Krichtal 2013).

In the 1780s the Arkwrights engaged more actively themselves in cotton brokering and Arkwright Senior supplied Nottingham hosiers with cotton from India (Fitton 1989). They also had London and Manchester partners not directly associated with slavery and Arkwright Senior was in business in Manchester and New Lanark with prominent cotton spinners who were also anti-slave trade lobbyists.

Perhaps via their influence Richard Arkwright Senior invested in three £50 shares in the abolitionist-led Sierra Leone Company in the early 1790s, although whether securing more regular supplies of raw cotton rather than replacing enslaved with free labour produce was the main motivation was unclear (Fitton 1989; Seymour et al 2015).

Here is the latest research on the Arkwrights and Slavery

The Strutts of Belper and Milford

The Strutts were leading cotton thread producers by the early 19th century and a significant body of their business records survive (Fitton and Wadsworth 1958). A detailed set of accounts from 1794 to 1817 reveal that during this time they sourced most of their raw cotton from the Americas where systems of production were heavily reliant on enslaved African labour. Information on numbers of bags of cotton purchased indicates that Brazil, known for its long staple cotton, was the most important source area, supplying almost half (46%) of bags, particularly from the Maranhão and Pernambuco regions. Just under a fifth (19%) were sourced from the West Indies and a further 17% from the areas of modern Guyana and Suriname on the South America coast where long staple cotton was also grown. The southern states of America accounted for just over a tenth (11%) with the first bags arriving in 1798. Just under 5% came from the Indian sub-continent (Seymour et al 2015).

More detailed information the weight of cotton purchased between September 1793 and September 1798 highlights the West Indies as a more important source than the bag information suggests. Over this period 45% of the Strutts’ raw cotton came from the West Indies, with the small island of Carriacou (part of the colony of Grenada) supplying almost a quarter (24%). The remainder came from Brazil (43%) and other parts of South America (12%) (Seymour et al 2015).

In their raw cotton trading, the Strutts dealt with both pro-slavery business owners and those who had abolitionist sympathies. An analysis of the Strutts’ raw cotton purchases via Liverpool between 1794 and 1802 indicates that over half (57%) of the bags, purchased were supplied by merchants involved in slave trading or ownership of enslaved people. Their most important suppliers were John Bolton, the Earles and Thomas Tarleton all extensive slade traders and owners of plantations and enslaved people. Tarleton supplied cotton exclusively from Carriacou where he owned a large cotton plantation, Mount Pleasant, worked by 227 enslaved African people in 1790 (Seymour et al 2015); Seymour 2018).

The Strutts included both pro-slavery figures and abolitionists in their family and friendship circles. Joseph Strutt’s (1765-1844) brother-in-law, William Archibald Douglas went to West Africa in the 1790s to make his fortune as a writer for the Company of Merchants Trading with Africa – the main British slave trading organisation of the period (Birmingham Archives). Conversely there are several reports of the Strutts supporting abolition of both the slave trade and slavery itself, with MP Edward Strutt (1801-1880) presenting abolitionist petitions to parliament in the early 1830s (Seymour et al 2015).

The Evanses of Darley Abbey

While work is ongoing on the slavery connections of the Evans family (Legacy Makers project), what is known to date indicates that they were heavy users of raw cotton produced by enslaved African people.

Their main raw cotton supply areas in the 1780s-1800s, were the West Indies and Brazil, with some Sea Island cotton from the southern states of America sourced after 1804 (Lindsay 1960). Supplies were imported via London, Liverpool and Portugal.

The Evans’ account with Liverpool cotton broker, Nicholas Waterhouse, for 1799-1800 reveals substantial raw cotton purchases, with around half supplied by known slave traders or plantation owners, and John Bolton again a core supplier (Seymour 2018).

Yet Walter Evans (1764-1839) of Darley Mill was another Sierra Leone Company investor, with 5 shares. He married Elizabeth Evans (1758-1836, née Strutt), widow of his half-brother, William, who had both radical and anti-slavery sympathies. Elizabeth’s son William (1788-1856), by her first marriage, was an active and persistent abolitionist. He was a director of the African Institution (the successor organisation to the Sierra Leone Company) and a frequent anti-slavery petitioner in parliament where he supported Buxton’s 1832 call for the immediate abolition of slavery (Seymour et al 2015).

Next Steps

The Derwent Valley Mills Partnership is committed to the development of further on-line resources which promote understanding of the histories and legacies of transatlantic slavery in the Valley. It is currently engaged in ensuring the availability through its website of the materials included in the DVMWHS Visitor Centre at Cromford Mills which promote understanding of the Valley’s relationship with transatlantic slavery and its current legacies. These materials were developed in collaboration with people of African and South Asian heritage through the Global Cotton Connections project and its partner organisations, Slave Trade Legacies (now Legacy Makers) and Sheffield Samaj and associated groups.

The DVMP is committed to the support of research and public engagement activities which promote the creation of further knowledge about the Valley’s involvement with transatlantic slavery. It is currently supporting the work of the Legacy Makers; National Lottery Heritage Fund project focused on Darley Abbey and the Evanses.

Global Connections Objectives

The DVMWHS Research Framework has three Strategic Objectives which identify areas for further research. These are:

- 1D Investigate how the Derwent Valley and its heritage provision is viewed by British diaspora groups, particularly those of African and Indian descent;

- 11A Assess the position of the Derwent Valley cotton industry in terms of the Empire, the slave trade and the pressures of global demand and supply;

- 11C Assess the impacts of industrial developments in the Derwent Valley upon the fabric of society in Britain, the Empire and across the globe.

To view the research framework visit: https://flickread.com/edition/html/index.php?pdf=57bdc0361e834#1

The latest Management Plan for the DVMWHS includes the following actions:

2.1.10 Continue to develop and grow links with other World Heritage Sites and explore other international links which help to communicate the Outstanding Universal Value and global significance of the DVMWHS, including less positive themes, such as slavery.

2.3.2 Seek opportunities for jointly delivered formal learning projects which link the DVMWHS and its communities to other World Heritage Sites nationally and internationally with the key stories of the site (water, industry, textiles, social change, slavery etc.)

For the full management plan, visit https://managementplan.derwentvalleymills.org/

With thanks to Dr Susanne Seymour of the University of Nottingham for her extensive work in the development of this material, to Dr Helen Bates and Lisa Robinson for their contributions as leaders of Legacy Makers, Bright Ideas Nottingham.

For further information about these Projects:

Global Cotton Connections Project

Legacy Makers at Cromford Mill

Additional Resources for Teaching Children and Young Adults:

Anti-Slavery International – Slavery Then and Now